This post may contain affiliate links.

The Dutch are truly lovely people, but they really need to learn to be quiet when other cyclists (like yours truly) are suffering badly up climbs…

So, I’m back from France. I actually have been for a while, but I felt like I needed to do one last update on how the trip finished out. Also, I have some really cool pictures of cycling in France that I wanted to share, so this is an excuse to do that. Let’s get started.

Dutch Chatterboxes – more distracting than you can imagine

If this picture could talk, the loudest people in it would be Dutch.

Let me just put this out there right now. It’ll help you understand things better if you know that I am not at all a good climber on the bike. Yes, I do it all the time, but I’m far too big to be any good. I just sort of like the suffering.

On the more difficult climbs, it really does take every last bit of concentration I can muster just to force my body to continue cycling. If I were to take out all the swear words… well that would be really difficult. But if I could, my internal monologue on a climb would be something like this:

“Left. Right. Left. Right. Keep. Going. Just make it to the end of that guardrail. Left. Right. Great, there’s a butterfly. See if you can drop him. Left. Right. Left. Right… Nope…”

At times like this, the voices in my head are nothing but swear words. I gave you a family safe version.

Now imagine being deep in your pain cave, just trying to hold it all together, and suddenly you hear this casually rolling up behind you… VERY LOUDLY.

Mijn klomp raakt mijn ketting!

And it wasn’t just once it happened. It happened on every single climb. Pain. Pain. Pain. Pain.

Ik verbouw mijn windmolen!

And I knew they were Dutch because they would all be wearing jerseys that had “something.nl” emblazoned on them somewhere. The whole thing reminded me of the handicap radios from “Harrison Bergeron”, which were placed on those with above average intelligence so as to disrupt their thoughts. Only in this case,

Mijn zoon is vier meter lang!

Ugh. In this case, it was a handicap on the below average climbers (me). And now I’m thinking about Kurt Vonnegut, and how it’s been a while since I read “Breakfast of Champions”, and, well crap, this really isn’t helping me climb any better at all…

On the plus side though, the Dutch spectators are fabulously supportive of everyone, including the really bad climbers like myself. And they’d be among the first to offer you a beverage once you’ve reached the top (or perhaps before), so it all evens out.

Col d’Izoard – my absolute favorite

We rode a lot of the famous mountain passes in France, with names we recognize from the tour. But the Col d’Izoard was hands-down the most fun of the bunch.

Look at that, I just called a climb “fun”!

I don’t have anything bad to say about this one. It didn’t annoy me. It was beautiful. It was relatively free of vehicle traffic. The descent was a winding roller-coaster switch back of smooth pavement. And there was a little shack at the top that was selling sort-of-cold Cokes. (All beverages in France are just “sort of cold”.)

So – if you ever get yourself to France for a cycling vacation, put the Izoard on your list. It’s worth the trip.

Yep. This one was actually fun.

La Marmotte – Why did I sign up for this?

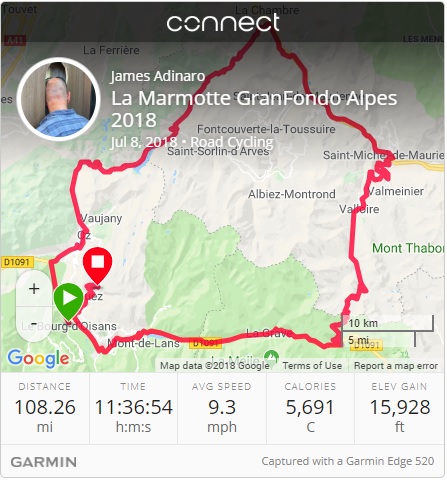

So the “signature event” of our trip to France was entry in to the Look Marmotte Granfondo Alpes, an actual European cycling event. Since this event was advertised as having about 16,000 vertical feet of climbing, and since we’ve established that I’m not a good climber, I knew it was going to be difficult. So my strategy to prepare for this event was simple.

I ignored it.

Boy am I glad THAT’S over…

Let’s just say that “bluffing it” through the most difficult athletic event you can find is *not* a strategy for achieving peak performance. Yes, I did finish. But it was only stubbornness and self-loathing that pushed me over the line. It wasn’t pretty. Let’s run through a quick course recap.

The event started off at 7:00 AM in the town of Bourg-d’Oisans, which is at the foot of Alpe d’Huez. Our hotel was at the top of the Alpe, and I should have known I was in trouble when it took me 30 minutes to ride *down* the mountain I’d be climbing 100 miles later that day.

It was kind of tight at the starting line. I should have gotten used to this. Apparently, the way of things in Europe is to ride as close as humanly possible to other riders – even if there are 75 acres of car-free closed road to your left. I never got used to this. It must have something to do with being American. We’ve got lots of space here! Heck, I even moved West so that I could have more space! And these guys weren’t drafting either. They just wanted to ride handlebar to handlebar with me and make me claustrophobic.

The first obstacle on the route was the Col du Glandon. In discussing the route with Steve ahead of time, neither one of us gave this climb much thought. As it came first and was one of the shorter climbs, we just figured we’d breeze over it. Wrong.

Not easy.

Clearly we hadn’t given the Glandon the respect it deserves. It’s longer than we thought, steeper than we thought, and though it was still within my ability, it did its job of draining the tank so that I’d be good and tired for the remainder of the day.

I like this picture because it makes it look like I’m leading all those other cyclists over the climb. Nothing could be further from the truth. What you can’t see is the elderly (probably Dutch) gentleman with a walker passing me to my left. Thank goodness we can crop photographs easily these days.

After the Glandon, we rolled through the countryside long enough to catch our breath, and then we started the ascent of the Col du Télégraphe. This col is really just part of the ascent of the Col du Galibier, which is truly massive. Most of the riders grabbed a quick water from their support teams, and went right over and started to attack Galibier. Not me. I walked to the café across the street and ordered a sort-of-cold Coke and watched them roll by for a while.

They had police there trying to keep traffic sane, so I couldn’t get a picture of the sign at the top, but it’s that little blue thing in the middle of the picture.

After a short descent off the Télégraphe, the road turned up again and it was time to climb to the high point of the day: the Col du Galibier. It was on this climb where I realized something about “Paul and Phil” who are the English-speaking commentators you typically hear on the Tour de France… they’re lying.

You’ll often hear them say something like “Well, this climb starts off at about a 5 or 6 percent gradient, and then it kicks up for a bit in the last kilometer.”

That’s a lie. It’s always 10 percent. Always. The whole way. All climbs in France (except the Lauteret).

Uhhh… This 10% crap is going to be over soon, right?

Here’s the deal. Some of the signs may say “next kilometer 6%” or whatever. But it’s really 10 percent for 96 percent of the kilometer, and then slightly downhill for the last 40 meters. Or something like that. It’s just awful.

Nope. Still 10%.

Well, the climbing is awful. But the scenery is spectacular!

And check out these people! They had the best boondocking spot in history! It was so awesome, I had to stop (because, you know, we have an RV blog) and take their picture. Stopping is a big deal on a climb like the Galibier, because you’re not totally sure you can get your bike going again once you’ve stopped.

But I did, and I made it to the top. Had a snack, and headed down the hill. This was no ordinary descent. It was – very literally – 35 miles downhill. Part of this downhill was what I’m calling the “Tunnel of Terror”.

Imagine this: you’re headed down hill at about 35 miles per hour. The pavement turns choppy. You round a corner, and BAM… there’s a tunnel. You don’t have time to take off your sunglasses, and the road is so rough so you can’t take your hands off the bars once you’re in the tunnel. The tunnel itself is about a kilometer long. And the lights in the middle of the tunnel don’t work! You’re just falling through the blackness, counting on gyroscopic stabilization to keep you upright because you can’t really tell which direction upright is. The only thing you can hear is the wind in your ears and the large truck bearing down on you from behind.

And the Dutch, of course. You can hear the Dutch sharing tulip stories, or dike-fixing tips, or whatever it is they just have to talk about when you really need to concentrate.

But once we’d made it through the tunnel of terror, there were just a few more minor tunnels in the way before the last climb of the day to the finish line. The Alpe d’Huez.

This is what the Alpe d’Huez looks like when you’re so sick of climbing that you get off your bike for ten minutes and throw a tantrum.

This was the second time I’d climbed the Alpe, and it was by far the slowest. At the foot of the climb, my Garmin was showing that I’d already ridden 100 miles and climbed 12 something thousand feet. I was in no shape to set any kind of personal record.

Let’s not do this again anytime soon.

But I DID set a personal record. It was on the Alpe d’Huez that I set my new personal record for the lowest sustained speed on a bicycle without falling over! 2.4 miles per hour. That’s slower than a slow stroll. It was brutal, and took me over two hours to climb what the pros climb in about 45 minutes.

But eventually I did reach the finish. Here’s my route and data for the day:

I will say this about the Marmotte: the French really know how to put on a bike race. (Go figure) This was one of the most organized, well staffed, and professionally run events I’ve ever had the opportunity to participate in. There were literally thousands of participants, and it takes some real planning to get that number of people through a hundred mile suffer-fest. All of the rest stops were where they were supposed to be. They were all well stocked. The course was obviously marked. Most of the roads were closed. Even the swag was pretty sweet. It was really just a pleasure to take part in, and I’d recommend it if you’re ever looking for a way to punish yourself and utterly ruin a European vacation.

After that, it was time to eat anything I saw, and then just Steve and I getting our butts back to Paris. They call Paris the “City of Light”. We got to experience exactly what that meant as our room on our last night in the Paris Hilton was spent in the “Kenny Rogers Roasters Suite”.

Late night at the Paris Hilton.

Seriously. This was at 11;30 PM. They don’t call it the “City of Light” for nothing!

But we weren’t there long, and then it was time to (barely) catch the flight back to the states. And here’s a pro-tip for you. If you ever need to fly out of Charles de Gaulle… allow yourself 3 or more hours before your flight to get through that airport. It’s a beast! We allowed two hours, and barely made it.

Miraculously, even our bikes made it home!

Fin

I agree that ALL climbs in France are 10%! In June we climbed Col du Tourmalet, 10% all 15km! Neither Phil or Paul are math majors thus are underestimating actual grades. However long a long decent does increase overall average speed and makes the Garmin data look good (unless you look at the lap breakdown).

Keep up the good work, both on the bike and the blog!

Someone who knows!

We didn’t do the Tourmalet, but it’s good to know it obeys the standard 10% gradient rule…

This looks like a lot of fun and something I have always wanted to do, the climbing looks brutal! It looks like Trek travel which I have heard great things on the Europe trip.

Maybe next year, I will do San Francisco to San Diego this October with Challenged athletes foundation. 630 miles.

Sign me up for next year. I guess I need to start training today. That would be learning to speak Dutch.

Lol. Well, that means you probably climb better than I do!

You probably know by now that “Marmotte” is the french word for “Groundhog”.

So probably your own personal “Groundhog day” hell will be to forever repeat this grueling day…LOL. Of course, by forever repeating this day, you will become the king of the mountain after a thousand or so repeats…

You are truly an inspiration to all us cycling wannabee’s.

I even saw a Marmotte while we were over there cycling!

(But I have no interest in repeating the experience…) 🙂

Pain, struggle, agony, crowded roadways, (and some complaining)…… I think the only thing missing to make it a complete “French” touring experience is this guy:

https://sports.gunaxin.com/wp-content/uploads/gallery/el-diablo-tour-devil/tour-de-france-devil-didi-diablo-78.jpg

I would have LOVED to have seen that guy over there!!! Would have made the trip complete!